The Three Stages of a Startup in Brief

The Western Balkans' key indicators on education, skills and employment 2022 (KIESE) portray an increase in the educational attainment levels.

While this is a general trend in the Western Balkans too, the picture is far from rosy.

The KIESE is a collection of crucial statistics that provide a review of developments in the field of education, skills, and employment in partner countries. In this post we focus on providing an overview for education and partly skills.

The KIESE allows comparing trends against the European Union averages on key indicators on education and skills.

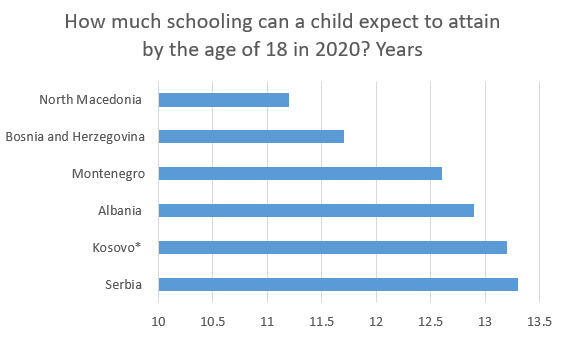

Expected years of schooling

The calculation of expected years of schooling is a crucial aspect of educational evaluation and planning. It is determined by summing up the age-specific enrollment rates between the ages of 4 and 17.

These enrollment rates are based on accurate approximation methods, which take into account school enrollment rates at various levels.

Here we look at overall number of years a child will spend in education.

The above chart indicates slight differences in the number of schooling years children can expect to attain in the region.

In North Macedonia a child, on average, will receive 11.2 years while in Serbia the number goes up to 13.3 years.

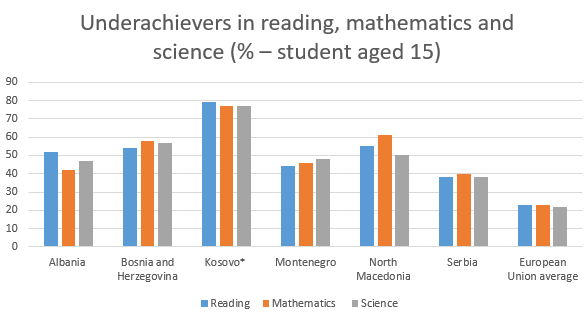

Underachievers in reading, mathematics and science

Low achievers in reading are 15-year-olds who are failing Level 2 of the OECD Programme for

International Student Assessment (PISA) scale for reading.

The indicator measures the youth population most at risk due to a lack of foundation/basic skills.

Among the Western Balkan economies, only North Macedonia witnessed a sizeable decrease in the share of underachievers compared with the previous rounds of the survey (2015). The focus is on reading, mathematics and science.

Interestingly, there has been no overall improvement in the learning outcomes of students in the wealthier OECD countries.

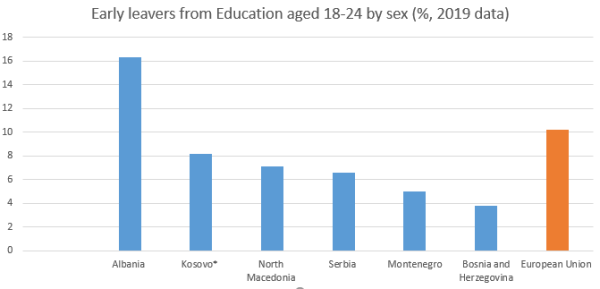

Early leavers from education

Early leaving from education and training is another major issue.

It is defined as the percentage of the population aged 18-24 with (at most) lower secondary education who were not in further education or training during the 4 weeks preceding the survey.

Five out of six Western Balkan economies display early school leaving rates well below the EU average.

Compared to the last report, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia have seen notable improvements.

Albania is significantly above the EU average and has to find a way to tackle this issue in the future.

Trends in higher education

The report portrays improvements in tertiary attainment, especially for women.

In Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia nearly 40% of their 25 to 34-year-old population have completed higher education.

Note that the EU average stands at 41%.

Albania is closing the gap too, although it will take time due to a lower starting level.

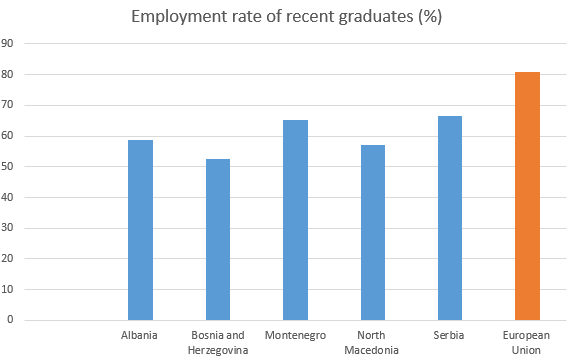

Young graduates with higher education degrees have a higher rate of being over-skilled in all countries covered by the report.

In Serbia some 50% held jobs requiring lower levels of formal qualifications, followed by 40% in Albania and Kosovo*, and 33% in North Macedonia.

Training for life

Over the last decade there has been minimal progress

The share of population participating in training is roughly the same throughout the last decade. In most countries with data available it stands at around 1%.

A regional outlier is Kosovo* with around 5%, while the EU average is 11%.

Around 20% of adults aged 25-64 in Serbia participated in non-formal education and training. This is twice as higher as in the other analysed economies (roughly less than 10%) but also half that of the EU average

Towards improving key Indicators on education and skills

Despite many improvements, the region's policy makers should consider creative ways of raising the bar further.

For example, standardised tests such as OECD PISA indicate that many students go to school

without learning.

Another area of concern are girls who outperform boys in learning, but underperform on years of schooling.

Around three quarters of students aged 15 in Kosovo* are at risk of gaining foundation skills.

It is slightly better in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia where around half of the students fall under this category.